The writer, critic, and photographic historian on the essay and his postcard collection

By Lucy Schiller, Editor

Ever since I read his expansive book Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, Luc Sante has been on my mind. Sante is a deft and keen-eyed writer able to sally, in an essayist’s fashion, through layers of history and “evidence” in order to produce his own ambitious work. Low Life (1991) resurrects the realities and landscapes of underclass Manhattan in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Sante’s varied sources provide him with a wild and wide range for what becomes a literary-political act against cultural amnesia. I thought, reading it, of James Agee’s “Brooklyn Is”—a strange comparison, for Agee wrote from his moment, staring into Prospect Park, and of course Sante writes from his very different one, backwards in time. But there was something to it. Both essayists are fixated on the narrative possibilities inherent to photography, and the limitations, too, of the medium.

Sante has since written quite deeply into photographic history and the visual; he has published a book of early New York Police Department crime scene photos (Evidence, 1992), a memoir of his Belgian childhood (The Factory of Facts, 1998), a long essay on Agee’s old photographer friend Walker Evans (Walker Evans, 2001), a book on vernacular photo postcards (Folk Photography, 2009), a book on portrayals of baptism (Take Me to the Water: Immersion Baptism in Vintage Music and Photography, 2009), and a typically (for Sante) deeply researched book on the underbelly of Paris (The Other Paris, 2015). He has also written for too many outlets to note here and composed too many introductions and prefaces to cite in full, but I will remark that he has served on staff as a crime critic, photography critic, book critic, and film critic at different magazines, a fact which testifies, I think, to the sprawl of both his interests and his expertise. Sante now works at Bard College, where he teaches writing and the history of photography. I spoke with Luc Sante over email about the essay and his real-photo postcard collection.

Essay Review: Just what is a real-photo postcard, and why did they become so popular? Where can we find real-photo postcards?

Luc Sante: A real-photo postcard is a card that has been printed in a darkroom, as opposed to on a lithograph press, and necessarily in a small edition for local consumption. In the United States they peaked, along with the broader postcard craze, between 1905 and 1914, and were produced in dwindling numbers until about the 1940s. They can occasionally still be found in junk shops and flea markets, but nowadays most reliably on eBay.

Essay Review: Why do you deem these postcards important? What do they tell us?

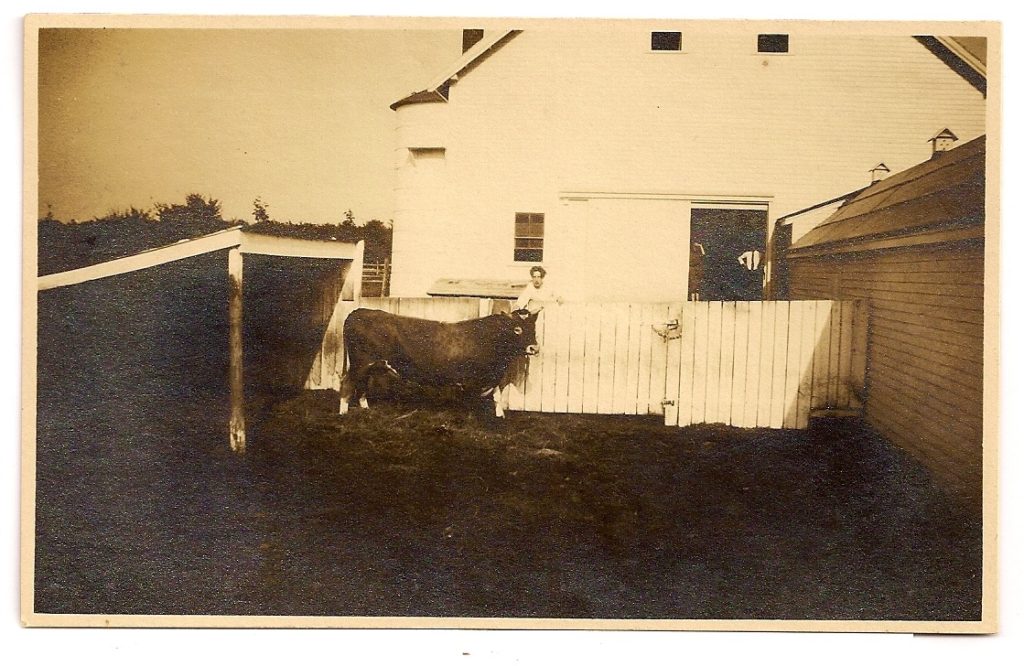

Luc Sante: They represent an application of photography that was spontaneous, independent, decentralized, ad hoc, not beholden to any canon or standard. It was a purely rhizomatic phenomenon, if I can put on the high hat for a second–there was absolutely no hierarchy possible in this art form. It arose in a thousand small towns; the conversation that accompanied it mostly happened by word of mouth; there were no prizes or juries or academies. And the market was basic: cards cost less than a nickel. Practitioners neither broke nor followed rules–the rules were whatever they decided them to be. The cards had genuine utility value: they conveyed news of various sorts on their fronts, and their backs were employed for communication of any damn kind, usually unrelated to the image. I should note here that quite unlike the idea we have of postcards from later in the century, they were in no way intended for use by tourists–there were no tourists in most of these places–but were meant for use by locals, usually isolated, to communicate where they were to people far away. The phenomenon is in some ways wildly diffuse: without a hierarchy, there is no vantage point from which to view it, let alone arrange it into a pleasing shape. At the same time, because of its historical limitations, it is highly concentrated. It’s as if the entire history of bronze casting or the heroic couplet or flamenco had been compressed into a single decade.

Essay Review: You’ve compared these postcards to folk music in that they spread news of cultural events, of disaster, of figures, of political movements. But, as you say, “they’re also about making something of it, meditating on important events.” When we consider the essay in its many forms, one thing that seems to be a commonality is this sense of a meditation, this sense of “making something” by rolling our thoughts around what is there in front of us. Do you see these postcards working in a similar way? How can a postcard, which most people would imagine to be a static, trivial thing, hold this power?

Luc Sante: The differences between the cards and the essay are more apparent than their similarities. The cards were made quickly–the more urgent the subject the quicker they had to be shot, developed, captioned, printed, and put on sale. Nevertheless they were charged with an editorial responsibility: they were to stand as the community’s assessment and eventual memory of an event. In many ways they were the equivalent of newspaper photographs, in a time and place where newspapers lacked the means to reproduce photos. But because of their physical qualities–they were contact prints, which meant they had the ability to convey masses of information within their 3″ by 5″ frame, their backgrounds filling with additional detail when you magnify them–they allowed for broad personal leeway on the part of their makers. You begin to realize how much when you find an event that was covered by multiple photographers, such as the Herkimer, New York flood of February 1910, which produced dozens of cards shot by five photographers working independently of one another. You see that one is focused on solids, another on liquids, a third on humans–the shape of the event looks different in each hand. Sometimes you find a photograph of some small-town main street that conveys pride and a sense of belonging, and sometimes you’ll find a similar picture that conveys alienation and defeat. Also don’t forget the importance the cards had in their time and place; they were not thought of as static and trivial but as at the very least chips that allowed their senders to play in a much larger field, all cards mailed inviting cards to be received, from out there. Each card was charged with the complicated emotional business of the local citizens, and broadcast to the world. That picture of a burning barn says “here we are” and “that’s our big news” and “it looked so pretty” and “we’re fucked.” That, in one metonymic form or another, for all 238 potential customers of Bob’s Drugstore and Photo Gallery.

Essay Review: You write that “the only human activity I haven’t seen represented on a photo postcard is childbirth.” And it’s true—we see baptisms, death, disaster, dances, politics, and a good bit of the (now) inexplicable. I was struck by this breadth of activity represented, of course, but also the patterns moving through the collection. It reminded me, actually, of Charles Reznikoff’s Testimony, these tight but expansive glimpses of American life and lives swelling forth in startling configurations. In Reznikoff’s work, the particular begins to take on a larger significance, and a larger portrait and history of the United States emerges. Can you speak to your arrangement of these photographs at all? What were you trying to convey by presenting patterns within folk photography? Were there any patterns that surprised you?

Luc Sante: I’m so happy you brought up Testimony. I didn’t in my text, although I mention it often–I did so in my introduction to Félix Fénéon’s Novels in Three Lines, which also has many similarities to these cards. I edited them the way I edit everything: as quickly as possible, going purely by the back brain. I was less concerned with advancing an argument than with creating a flow. It’s true that the sequence begins in a sense with stability and ends with disaster. Then again, in this early-20th-century rural world, disaster is often played for dark comedy and stability sometimes looks worse. But emotion is something that usually has to be inferred from the pictures. Now and then people will be laughing, and sometimes they look bottomlessly sad, but you don’t often get representations of anger, for example, whereas Reznikoff’s depilated legal summaries are made up entirely of human drama, the reverse side of the coin. As far as patterns surprising me, they did from the first encounter. The first cards I saw were of the American incursion into the Mexican Revolution, in Vera Cruz in 1913, and I couldn’t believe that I was looking at first-generation photographs, printed as postcards, of such an event. The cards have never stopped surprising me, even though I know most of the templates by heart by now.

Essay Review: Can I quote you from another interview? You said that “I often think of what I do as wide poems…I write prose with a poet’s head.” What can your type of “wide poem” include? I think of the late John Berger, who wrote such poetic but completely lucid prose about art, about ways of seeing, about photography. When we use prose to consider the image, is there a kind of prose that to you might be most successful, and is it a version of the “wide poem?”

Luc Sante: I guess in that “wide poem” reference I was thinking of prose that could be as fluid and subjective and intuitive and subcutaneous and driven by language as poetry, prose not manacled to narrative or argument or thesis. I’m not sure my text for this book has that, since it does put forward an argument. But I’m always looking for prose that conveys the visual in ways that do it honor. Berger’s work certainly qualifies. When he died I realized all over again how he was the very first writer to make me think about writing on photography, specifically with his little essay on André Kertesz’s “A Red Hussar Leaving,” which was published in the Village Voice when I was in my early twenties. I was about to list a whole bunch of other writers here, but to my surprise I couldn’t think of very many: Manny Farber, John Ashbery in his art writings… There are others, but not a lot. That’s not to say there isn’t brilliant writing on art or even photography, but that so much of it evades the responsibility of accounting for the visual. It’s so much more natural for writers to go the way of narrative or argument or comparative ranking or refutations of other writers or (heaven help us) theory. To convey the visual successfully is hard: the prose has to be very simple, concise, and material. It’s a form of synesthesia, really.

Essay Review: Why did you choose to use your particular, personal collection of postcards for this book? Why not a broader and more external survey?

Luc Sante: When I started collecting photo postcards I was alarmed. I’ve never wanted to be a collector of anything. So I made it a condition that I had to write a book about them, and then quit. I intended the book to be a thoroughgoing history, including vertical surveys of towns, capsule biographies of photographers, an attempt to corral statistics, notes on dating pictures–the whole ball of wax. But before I could get far enough I was beaten to the clock by Robert Bogdan and Todd Weseloh’s Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People’s Photography (Syracuse UP, 2006), which, well-researched and engaging, answers most of that description. So my book became perforce an extended essay with a bunch of pictures. I had always, in any case, intended to use my own collection as the skeleton, and collected cards for thirty years with that in mind. I was looking for exceptional cards, but also typical ones, and whenever I spotted a pattern I had to obtain several examples. I started buying cards when they cost a quarter apiece, and by the time eBay came around I was selling every tchotchke and collectible in the house to buy more before prices rose beyond affordability. My point in doing this was that because of the phenomenon’s diffuseness, all that I would garner by dipping into the great collections out there–Leonard Lauder’s or Andreas Brown’s or Anthony d’Offay’s, for example–would be a lot of exceptional pictures, to the detriment of the typical, and the typical is the heart of the phenomenon.

Essay Review: Is there an image in this collection that feels to you the crown jewel (or is your favorite)?

Luc Sante: Not exactly, for the reasons I’ve just cited. But there is a picture that tears me up every time: the one of the mother holding her dead baby in her lap. I found that in a drawer in a junk shop in Akron, Ohio about twenty years ago. There are many postmortem cards, if notanywhere near as many as there are postmortem photos in various formats from the previous century. But seldom have I ever seen an expression of such pure and total sorrow in any of them as the look in the mother’s face. And her hand, dangling, sapped of strength. The cards are usually emotionally reticent, but this card is a cry.

Essay Review: What do you look for when you are collecting real-photo postcards? Is there a quality that you do not find interesting, that turns you off of bringing a postcard home (besides, of course, a prohibitive price)?

Luc Sante: I haven’t collected cards in years, and I miss it sometimes. One thing I miss is the pure rush of looking at tens of thousands of images very quickly. When you do that you naturally develop a set of visual clues, things that can register in an instant and can sometimes indicate an interesting picture. Certain kinds of lighting. Also night photos, certain shallow spaces, the presence of signage, unusually long or unusually lettered captions, for example. But that kind of intensive crate-digging is grueling, especially after hours of flipping through 25-cent boxes. You have to go over and ask to look at the high-prices binder, so you can remember what a good picture is supposed to look like if you haven’t seen one in a while. But then some image hits you between the eyes and you remember what you’re there for.

Essay Review: Do you think that writers can learn from the photograph? What about nonfiction writers, specifically?

Luc Sante: I’m not sure that photographs can tell you how to write, but they can give you a lot of deep background, at least. These pictures are where you go to fill in a million particulars about how humans were and are. You get a sense of the vastly different sense of time enjoyed by their subjects, and of the lightly populated and highly circumscribed world they inhabited. The cards contribute to the history of postures and body language, facial expressions and social manners. Historians of vernacular architecture can learn a lot from them. You look at one-block towns where the main drag is wide enough for four lanes of modern traffic, plus parking, and you have to wonder how much they suspected of the future back then. The cards talk about baseball, evangelical revivals, snow carnivals, railroad strikes, church socials, race riots, vaudeville, animal husbandry. Most of what you see is solemn and formalized, even if the people pictured are wearing overalls and rubber boots. Everybody pretended they’d gone up in an airplane, but nearly everybody had taken a turn at the wheel of a car once. Unspeakable things went on sometimes beyond the bushes, but you only get occasional hints of it in these pictures. You can enhance the historical ambiance by reading George Ade, Ring Lardner, Booth Tarkington, Sherwood Anderson, early Gertrude Stein, plus comic strips and movies. Anyway, for me it’s about recreating a time–I’m endlessly fascinated by the ways in which one year will be emotionally different from the next–and also about peering into lives. I can never get enough of lives.

Essay Review: I’m interested in thinking about the parallels between the essay and photography. Some essayists, like James Agee, have found photography to be an occasionally imperative part of their work—in Agee’s case, in particular, he said that he found language insufficient to relay the experience of Alabama tenant farmers (though he also said he wished he could bring back dirt clods for his readers so that they could better understand the lives of the farmers. Maybe he felt photography, too, to be insufficient to his and Evans’s huge task). There is a very easy analogy to be made between nonfiction and photography—both purport to tell the truth—but that seems to me to be a very simplistic and narrow way of comparing the two modes of telling. When you write your essays, particularly the ones in which you are moving through time and space, exploring the particularities of New York or Paris, is there any photographic sense to how you work or think? Do you think there is something photographic in the impulse of nonfiction?

Luc Sante: I love to describe photographs, and do it often enough. But I don’t take a lot from them into my writing, except in a more generalized sense of style and concision. When I write I’m if anything cinematic, and that because of the cutting more than the photography. And also musical, in controlling the dynamics; culinary, in throwing in ingredients; and painterly, in setting the terms of the frame. Note that these are all physical activities, painting included. They are moving forward. Photography is static. It is the subject, not the method.

Essay Review: How would you like to see us write about photography or the visual as we move forward? What new is there to do?

Luc Sante: That’s a hard question to answer. I have no guidelines to lay down. I want to see passionate non-academic, non-journalistic writing about photography, a lot more than I’ve been seeing lately. I always appreciate being made to care in a new way about work I already know, as much as I’m eager to learn new stuff. As I said above, I’m grateful for writing that actually takes on the visual qualities, something I’d also like to see more of in art and movie writing–I’ve been saying that about movie writing for forty years. Back then, alternative weeklies staffed by recent English majors tended to give us dense literary interpretations of movies without any indication the thing was shot with a Bolex in a north-facing hotel room on a rainy day with every lightbulb in the house blazing, let alone had been shown x-large for an audience of people who might be talking back to the dialogue and throwing things at the screen. I’d always like to hear more about the real.